Marc-André Hamelin

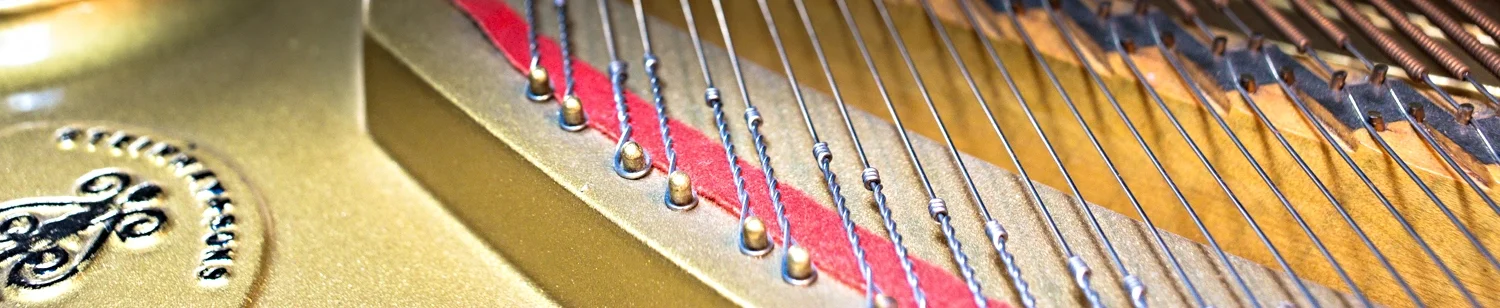

/Photo by Fran Kaufman

In the coming months, we will be featuring interviews with musicians of various backgrounds. If you are a musician and would like to be featured in our series, please contact us at thecounterpoints[@]gmail.com. A complete list of our interviews can be found here.

Marc-André Hamelin was born in Montréal, Québec. An Officer of the Order of Canada, Hamelin has devoted his life to the execution and promotion of the extended piano repertoire. A virtuoso of uncommon ability, his recorded output is both daunting and a monumental contribution to musical art. Below is the transcript of our November 8, 2013 conversation with the composer-pianist Marc-André Hamelin.

EH: A pupil of Alfred Cortot, Yvonne Hubert was your teacher in Montréal. Her other students include: Louis Lortie, Janina Fialkowska, Andé Laplante, and Horowitz pupil, Ronald Turini. What was Mme. Hubert like as a person, and what was her greatest contribution to your pianistic development ?

Hamelin: As a person, I must say she was wonderful. She was not one of those teachers who was psychologically very difficult to deal with. Her help was very constructive, but she demanded a lot of you – that’s really how I felt when I was with her, from the age of eleven to seventeen, inclusively. There’s no question that she helped a lot, but there were limitations as well. The teaching was within a certain framework, and I think originality was not necessarily… encouraged (laughs). But there was a lot of attention to sound and detail.

I remember one of the very first lessons I had with her was on the Fourth Three-Part Invention of Bach, the one in D minor. At the time, I didn’t know anything about polyphony. She made me to listen to every little strand, and, of course, she was pointing out the obvious, but these things weren’t obvious to me at the time. I remember leaving the lesson completely exhausted – it’s a lot to absorb at that age – as I hadn’t developed any kind of maturity at the time, but it’s just a small example of how meticulous she was about sound. She had some very original suggestions about fingering and technique. Any one of her student can attest to – well, she sat to the right of the student – the fact that she could demonstrate right-hand passages faultlessly with her left-hand (laughs).

EH: Your piano technique and physical mechanism are the envy of piano students around the world. I must ask the question on everybody's mind: how much of this came naturally to you ? At what age did you begin thinking of the problem of piano technique and how to solve it ?

Hamelin: Yeah, that definitely can’t be answered in a paragraph or less (laughs). To be perfectly honest, I was never really aware that I had any special abilities. When you have what you have, you don’t really think about what you don’t have; you simply work with what you have. And if you’re not in someone else’s shoes, you really can’t say. I never considered myself more able than anybody because I had problems just like anybody else. When I practiced, I solved problems, like any of my fellow students. I looked at my own work, and looked ahead, with blinders, almost.

That being said, my father was a very good amateur pianist, and he had a collection of books on technique. One of the things he had was a small volume of exercises by Rudolf Ganz, in which Ganz mentions the pedagogical work of the Swiss composer, Émile-Robert Blanchet, who wrote a ton of polyphonic exercises for one-hand. These exercises were a great help for finger independence, which I acquired early on. This might have given me somewhat of an edge, a facility to be able to knock any obstacle that was in my way. Of course, there were others as well. Another book he had was a collection of Busoni exercises, which is quite unusual, but they were effective and useful.

EH: At your level of proficiency and accomplishment, do you still work on matters of mechanics ? Are you, by any means, a compulsive practicer ?

Hamelin: Very rarely do I work on mechanics now. I tend to solve problems within the music itself. Now, that is my way of doing things, and I wouldn’t necessarily recommend this to anybody else; if you need to do technical exercises, you do them. The whole point of practicing is to get to know yourself, to know your weaknesses and to zero in on them and target them. It’s not really about employing anybody else’s formulas, because you really have to find what is best for you and what you need.

EH: Your recorded repertoire is amongst the largest of any living pianist and it covers a very wide spectrum. What is your process of selection ? Is there an intended purpose behind it ? And are you able to store, in the mind and in the fingers, most of these pieces after the recording sessions ?

Hamelin: No, there’s a substantial portion of my recorded repertoire that was learned for the recording sessions, and then basically forgotten. I wouldn’t say it’s the majority, but it’s a fairly good chunk of it. That should tell you, right then and there, that I don’t record for my own glory, so to speak. I mean, of course part of it is for career advancement, but more importantly, I want some of that repertoire - as much of it as possible - to remain and enter pianists’ consciousness and, hopefully, into the standard repertoire.

Whenever I record something, I always believe that it’s worthy of inclusion in the pantheon, and I would certainly like pianists to pay more attention to it. I think it’s ridiculous now, because the range of repertoire – or what’s considered ‘safe’ - is so narrow, even though there are pianists who are really trying to push the envelope. There is still a lack of attention, and there’s no reason for it. The piano repertoire is so rich, with so many wonderful things that still are not given their due.

EH: In the last two-hundred years or so, there’s been a trend veering away from the performance of contemporary works. Much of the public is not even aware that people are still writing today. Do today’s performers carry the responsibility of performing the works of their contemporaries for the well-being and future of music ?

Hamelin: I don’t think they should do it if their heart isn’t in it. But if they do feel something, a mission that comes from the heart to promote these things and to encourage composers to write, then of course they should do it. And there are more than a few pianists these days who do this, fortunately.

EH: And thank you for being one of them. In your opinion, who is a notably underrated composer whose works you would recommend for students to have a serious look at ?

Hamelin: I think it comes down to individual pieces. I think anybody who’s willing to really sink their teeth into a work like the Hammerklavier, which is a very interesting, different experience, should look instead at something like the Sonata by Paul Dukas, which, in my opinion, is a real marvel.

Medtner, also, has not yet been given his due, though there are pianists who are certainly interested in him. This is, of course, thanks in large part, to the publication by Dover of his complete Piano Sonatas and complete Fairy Tales.

EH: I’d love to hear your thoughts on Medtner, why you think he isn’t as popular as his classmates, Rachmaninoff or Scriabin. Do you have any advice for students who are trying to learn the style of Medtner ?

Hamelin: I think one of the reasons Medtner hasn’t had a chance is that his music needs very, very committed performances. If you play his works passively, the juice of his music is really not going to be extracted – it’s simply not going to come out. And maybe that’s been the problem – not least, but from Medtner himself, who I do not think was the best possible advocate of his own works. But that’s my opinion: I find him a little uninteresting and cold, sometimes. Also, at first, the thematic material is not of a kind that makes the greatest appeal, but if you keep with Medtner, I think he will take hold of you, and you’re very likely to become a fan.

EH: You’ll be performing his Night Wind Sonata in San Francisco, on January 31. What can you tell us about this work ?

Hamelin: First of all, I’m very grateful to San Francisco Performances for inviting me. They’ve been so wonderful, having me back so often through the years. I’m particularly keen on promoting this Medtner piece, Night Wind, because I feel it is a fantastic work that hasn’t been given its due yet. Admittedly, it’s difficult for both the performer and the listener. The work is quite dense, comparatively long, as these things go, and demands rather active listening. But it’s gripping, and I believe it should be heard much more than it has been.

EH: I must ask the odd question, is there a composer you simply cannot like or connect with ?

Hamelin: I’m not sure we would necessarily be talking about piano works, but I don’t feel any particular attraction to Copland, for example. I mean, I certainly recognize its worth, his aesthetic was very secure, and of course, I know that his work touches a lot of people, but it just doesn’t touch me. But about music in general, I can certainly name a few pieces that should maybe be given a rest (laughs).

EH: Like many of the composer-pianists that you’ve recorded, you, yourself, are a composer. What is your process when it comes to composition ? I’d love to hear your thoughts as a composer, what your approach is, and the style you most prefer to write in.

Hamelin: As far as the style, I can’t say there is one definite style. I probably feel most comfortable writing in a tonal idiom, with considerable, if not extreme chromaticism. However, one of my latest pieces, a Barcarolle that I’ll be playing in the San Francisco recital, is entirely atonal. It sort of has a tonal center of B-flat – it’s a B-flat bass – but what happens above is largely atonal. So I do feel comfortable in both languages, but I’ll say that it’s usually whatever language the idea comes in.

EH: How essential is the skill of composition for a student of the piano ?

Hamelin: It’s indispensable, really. First of all, it helps you feel a little closer to the person who created the works that you’re trying to interpret. The process of putting intangible thoughts into an imperfect system of notation - which is difficult enough, depending on your ideas - acquaints you with how best to express your ideas so that it is as clear as possible to the performer.

Every composer understands and uses the system of notation differently, and that’s what makes you appreciate the trouble they go through in doing so. It’s the vision of the composer that we have to determine, and not the absolute mathematical adherence of the score. In my experience, there have been occasions where I feel that a composer has not notated something as they meant to have it represented.

EH: He tragically passed away sixty years ago, in the mountains of San Francisco. I’m curious to know, what are your thoughts on the recordings and legacy of the late American pianist, William Kapell ?

Hamelin: I don’t listen to recordings very much now, to be perfectly honest. I listened to them a lot when I was younger. My father ran the gamut: a favorite of his was Josef Hofmann, but there was also Friedman, Rachmaninoff, Godowsky, Lhevinne, Moiseiwitsch, Paderewski, etc. I don’t know Kapell’s pianism all that well, simply because I didn’t listen to him very much growing up. But I do know his recording of the Khachaturian with Koussevitzky – and that alone, should suffice in branding him one of the immortals. That performance was electric, vivid, and it seems the piece cannot be played any other way. It’s so authentic and driven, so purposeful.

EH: Mr. Hamelin, it’s been a pleasure and an honour. Thank you for taking the time.

Hamelin: Thank you, Elijah. It was my pleasure!