Paul Jacobs

/Photo by Felix Broede

In the coming months, we will be featuring interviews with musicians of various backgrounds. If you are a musician and would like to be featured in our series, please contact us at thecounterpoints[@]gmail.com. A complete list of our interviews can be found here.

Paul Jacobs is the current chair of the organ department at the Juilliard School. In 2003, the Curtis and Yale alumnus was appointed to the faculty at the age of 26. A Naxos recording of Messiaen's 'Livre du Saint Sacrement' was awarded 'Best Solo Instrumental Grammy of the Year' in 2011, making Jacobs the first organ soloist to win the honor. Below is the transcript of our February 14, 2014 conversation with the brilliant organist Paul Jacobs.

EH: The organ has such a long and rich history. So many of the great composers of the past composed for it and knew it intimately. What happened to the organ and its incredible traditions ?

Jacobs: Some organists lost sight of the point of music-making, which is to stir the soul - or, at the very least, to entertain. They assumed a more dogmatic approach to organ performance, where there is a right and a wrong way, instead of a strong or a weak one. Over time, organists became more concerned about what their peers thought of them than general audiences. As their playing gradually became more 'correct', the audiences for organ music diminished. Personally, I would rather be offended by a musical interpretation than bored!

Audiences simply want to be moved. They are not preoccupied with questions of style. Style is of secondary importance, in my opinion. It is synonymous with fashion, and fashion constantly changes. A musician might make the voluntary decision to study historical performance practice techniques, but the main objective should always be to capture the essence of a piece of music, which, I believe, is fixed, unchanging, and immutable.

Hearing Wanda Landowska play The Well-Tempered Clavier on the Pleyel harpsichord - an instrument quite unlike its historical counterparts - is surely no less legitimate or compelling; hearing Mozart on a modern grand-piano is no less worthy, artistically speaking, than hearing it played on a more stylistically 'pure' forte-piano. Organists today must strive once again for that red-blooded music-making, on par with the finest pianists, violinists, and singers.

EH: How would you describe the difference between the essence of a piece of music and the style of it - which may be realized in pursuit of that essence ? Isn't it the work of teachers to pass on the essence of a given piece ?

Jacobs: I fear that many teachers are not geared enough toward helping their students capture the essence of music. I’m not talking about playing a piece competently. This is a very difficult concept to articulate or define. But the essence of a piece, I would argue, is not merely checking all the right boxes and playing music in an appropriately stylish or sensitive manner. Rather, it is deeply spiritual; it is something that speaks directly to the heart in a pure and real way. However one goes about doing this is of less interest to me. The essence of any work of art, I believe, attests to an immaterial reality which connects itself directly with the human soul. It's positively thrilling to experience.

EH: You’ve mentioned in the past how the organ repertoire opens a spiritual dimension in listeners, a most interesting subject that isn’t brought up often. Can you elaborate on the religious and spiritual dimensions of the instrument and what it means to you ?

Jacobs: I encountered the organ for the first time as a boy going to church. This seems to be a common experience amongst organists (laughs), though the organ is not limited to the sacred realm, and certainly has a very active life in concert halls and civic spaces around the world. I believe that the spiritual dimension of life mustn't be ignored; it is critical to being fully human.

We place great emphasis on our financial, physical, and mental well-being, but, it has become possible with our busy lives to neglect our spiritual health. There's the old adage about the two things one shouldn't discuss in public - religion and politics. Well, the fact is that our culture is utterly consumed by politics, publicly and privately; it occupies our daily discourse in newspapers, on television, on the internet, and in personal conversation. It's inescapable. But religious or spiritual questions are another matter. Though these timeless questions are always there, like an elephant in the room, they're seldom discussed or pursued, even among friends. They make us uncomfortable, and for good reason. Yet they are most important - not to mention the most interesting, as they define our worldview and can offer a sense of the Infinite.

As far as the organ is concerned, I suppose it reminds us of a philosophical, reflective bent of the human condition – something outside of ourselves, something ‘fixed’, something massive, something with an objectivity to it. While the instrument is capable in the hands of a sensitive organist to capture the most intimate human emotions – and it does this very well – its ability to penetrate the human soul to its very core is unique. When required, it can produce a marvelously terrifying effect, reminding us of the frailty and brevity of our lives.

Charles-Marie Widor, the 19th century French organist, once said, "To play the organ well, one must be filled with a vision of eternity,". This is not to say that one cannot have great fun playing the organ - just think about making music with your feet! - but I believe there is a unique dimension that the organ is able to capture that can offer an even more direct pathway to our spiritual core.

EH: What then do you picture when you are practicing ?

Jacobs: Usually I don't picture anything specific while practicing, but believe that the main goal of practice is to heighten one's powers to hear, with utmost clarity, how we honestly sound. Young musicians tend to dwell upon the physical sensations - analyzing how the hands and rest of the body look and feel in relation to an instrument. Naturally they're preoccupied with physical and technical demands, particularly in the initial stages of practicing. But, ultimately, music is for listening, and so, when I practice, I attempt to become, as much as possible, an objective listener. Good practicing should be aimed at elevating one's powers to listen, accurately and truthfully. Only after these dues have been paid can one become emotionally attached to the music.

EH: A subject that is on the mind of just about every musical journalist is the doom and gloom around classical music. In your opinion, is the future of the art form secure ? How would you describe the importance of this beautiful art form to younger generations ?

Jacobs: I assume you’re referring to the articles in Slate, The New Yorker, and such. There are legitimate reasons to be troubled by the direction of our culture. It seems that, whenever we read articles concerning the state of classical music, they tend only to address the topic in a vacuum, separating it from a bigger reality. For a clearer perspective on the health or frailty of classical music, we must examine it under the umbrella of the humanities.

How are the humanities at large doing in our society? Music falls within this much broader category, and, unfortunately, there's much documentation confirming that humanitarian pursuits are in decline. Our society gives preference to scientists, doctors, lawyers, business leaders, technology, and so forth, but far less value is given to subjects that cause us to reflect deeply on the human condition. We must try to understand why this is the case. The humanities include literature, history, languages, art, philosophy, religion and music - subjects that carry us beyond the here and now. Artists and musicians must become more explicit in their charge to reawaken in our age that basic desire that we all have for transcendence. An art form is only secure if there are those willing to sacrifice for it. Fortunately, there is an army of dedicated, intelligent young musicians who understand what is at stake. Not just classical music, but the very soul of our culture.

EH: The late critic and composer Virgil Thomson studied the organ through his days at Harvard and beyond. In your opinion, what is the role of the music critic in today’s world of declining newspapers and blogs ?

Jacobs: Unfortunately, I have not played any of Virgil Thomson's music, but I've high regard for what he’s left us, in terms of criticism, his other compositions, etc. As far as music criticism is concerned, I think the decline of the role of music critics is indicative of a general cultural trend: the ability, or desire, to listen critically. This is the unavoidable result of a culture that does not emphasize a proper music education or its vast history. If you don’t value the education, you’re not going to value the subject very much, regardless of how it makes you 'feel'. Consequently, everything has been reduced to a matter of personal opinion, where all positions are equally valid, without any critical thinking, crucial listening, drawing distinctions, etc. – I mean, these are the building blocks of the Western tradition going back to the Greeks!

We seem to have turned our backs on these important principles and they must be regained. We should strive to increase our expectations for what music can do for us in our lives. Then we'll be less satisfied with what the latest pop-star puts out – that’s not to say that one doesn’t have the right to listen to it – but I believe these pop hits are woefully incapable of offering a glimpse of all that music has been and has the potential to be.

A greater awareness for the rich history of music is something that must be regained. It's disturbing whenever I meet highly educated individuals who know no music before the Beatles. They must be encouraged to dig and search for the sake of unearthing musical treasures of the past; for this music continues to resound with tremendous force. But one must listen.

EH: One beloved pianist who continues to resound, associating himself with Bach and the organ, is the Canadian pianist, Glenn Gould. I’m curious to know, have you listened to his Art of the Fugue recording ? What can you tell us about his abilities and his understanding of the instrument ? Did he fare nearly as well as on the piano ?

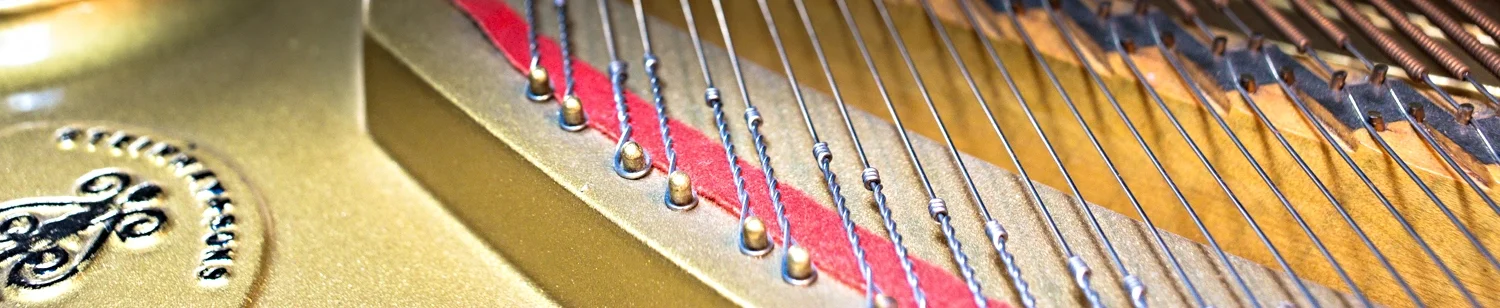

Jacobs: Honestly, no, (laughs). But I appreciate that we have a prominent pianist who was not fearful of playing the organ. Certainly he played the notes correctly and convincingly, but I tend to prefer Gould as a pianist. The piano and the organ are both keyboard instruments, but one often thinks about musical expression in a different manner. Touch - even on mechanical-action organs, where the keys are intimately connected with the speech of the pipes - plays quite a different role than on the piano. Organists must possess a refined sense of rhythm to create subtle accents and smooth phrasing. Additionally, they control expression pedals and manipulate a vast array of stops, which affects dynamics and color. This is known as the art of registration, and it's very personal to organists, particularly since the organ is a relatively un-standardized instrument. Before every performance, we spend numerous hours 'making friends' with the unique characteristics of a particular organ.

EH: Piano students are familiar with the piano works of Bach, Messiaen, Reger and many others. How crucial is it to know the organ works of these artists ? And who, for you, are some of the indispensable creators and interpreters of the twentieth century ?

Jacobs: If one aims to fully and comprehensively understand who these composers were, then it becomes important - if not necessary, to have some familiarity with their output for organ, since the instrument played a significant role in their creative life. For instance, it would be like someone saying, ‘I love the music of Brahms’, but not knowing any of his chamber music. It would be unconscionable! (laughs) To claim an affinity for Messiaen and remain ignorant of his major organ works, seems, dare I say, irresponsible. And the same can be said for Reger, and certainly for Bach. All of these masterpieces are just waiting to be discovered.

If we’re talking about Max Reger, there’s Rosalinde Haas or Isabelle Demers; I believe both capture the virtuosity and the passion of Reger’s writing. If we’re thinking of Messiaen, there are numerous interpreters of his work, but Jon Gillock and Susan Landale come to mind. It’s worth locating Messiaen’s own performances of his works. For Bach, of course, the possibilities are endless: Karl Richter, Virgil Fox, and Marie-Claire Alain, who passed away last year. There’s a world waiting to be discovered by music lovers.

EH: This Sunday, you will be performing a solo organ recital at Davies Symphony Hall. What can you tell us about these selections ?

Jacobs: Perhaps the highlight of Sunday’s performance will be Reger’s Introduction, Variations and Fugue on an Original Theme, Op. 73, a relatively unknown work, even amongst organists. Though this music, like much of Reger's output, makes extraordinary demands upon the performer, this is a truly magnificent composition, a splendid artistic creation. I would describe it as a fantastic adventure, a startling, colorful journey of the human spirit through life. It has its peaks and valleys, order and chaos, but it always brims with aural beauty. One seldom encounters such a high degree of transparency in Reger, who offers in this music a sincere, personal artistic statement. Reger is a notoriously difficult composer on both the technical and interpretative levels, but enormously rewarding to play. If the listener is willing to come on this musical journey, it could be – dare I say - a life-changing experience.

The first half will lure us in to the program with ease, beginning with a zesty Bach transcription - his Sinfonia to Cantata No. 29, followed by an intimate work of Mozart, K. 616 - originally composed for an elaborate mechanical clock in the final year of the composer's short life. Finally, the half concludes with the brilliant Sonata in D minor by the French organist-composer Alexandre Guilmant, who, in his day, was a favorite amongst American audiences. Hopefully this will entice the audience to return after intermission!

EH: Paul, thank you very much for taking the time. Welcome to San Francisco and best of luck Sunday.

Jacobs: Thank you, Elijah, it is my pleasure.